T: 01822 851370 E: [email protected]

RSN backs calls for better affordable housing in rural areas as part of Rural Housing Week 2023

This week the National Housing Federation (NFH) is running its annual campaign which highlights the challenges facing rural areas when it comes to housing. There have been some truly dreadful statistics released as part of this around the hidden homelessness crisis facing rural areas. This is despite news from the Government this week about energy caps and improved fundings for high-quality, energy efficient new affordable homes. Great headlines, but what sits behind them for our rural communities? I was invited by the NHF to guest blog about how what Levelling Up means for rural, something the RSN has done a significant amount of work on in recent years. As always there is a difference between policy that address rural challenges and policy written to ‘include rural areas’. As we all know, this isn’t semantics, it’s the difference between appeasement and real change. I would be interested in your thoughts...

Best wishes

Kerry Booth

RSN Chief Executive

The need for Levelling Up is greatest in rural areas – but has the Government missed the opportunity?

If you were to take England’s rural communities as a distinct region, more people live there than the whole of Greater London. New research has also found that the need for Levelling Up in these areas is greater than anywhere else in the country.

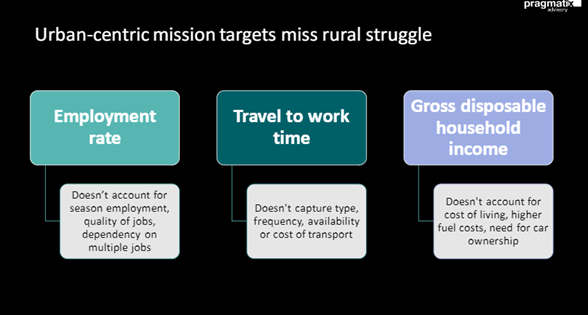

The Rural Services Network (RSN) commissioned a report last year which found that the metrics the Government uses to identify areas in need of Levelling Up support, don’t work for rural areas.

Rural as a region: the hidden challenge for Levelling Up revealed that the Government’s measurements were too urban-focused, as they didn’t account for disadvantage in rural economies within regions. This is around areas such as limited local employment prospects, poor transport networks and weak connectivity. Take jobs for example. According to the Government calculations, some rural areas are outperforming urban areas in employment figures. What their figures don’t take into account are the types of jobs, the quality of employment and the associated pay. Many rural labour markets are dependent on seasonal or part-time employment and have many workers over- and under-employed. The calculations also don’t consider the dependency of some workers on multiple jobs. Furthermore, just looking at gross disposable household income doesn’t account for the differing costs of living in rural areas, including higher fuel costs, the need for car ownership to get around when no public transport is available, or the cost of housing compared to local earnings. So, if the Government’s own workings out are causing an imbalance in funding, what can be done?

|

Time and time again, I hear that rural areas don’t want more money or handouts, they just want a fairer share of the pot. You can’t consider a region like Devon, where I live, as one geographical area. Of course, there are areas of terrific affluence. But there are also places where there is crippling deprivation. However, the latter areas are usually sparsely populated and simply don’t ever see the Levelling Up funds. Therefore, reducing the gap between regions will not lead to true Levelling Up. It just further increases the gap between areas within the region. So, I ask again, what can be done?

Well, let’s start with housing. At RSN we are calling on the Government to deliver the right homes, in the right places for our rural communities. House prices are less affordable in predominantly rural areas than their urban equivalents (excluding London). In fact, according to the Nationwide House Price Index for June 2023, rural areas have seen a 29% rise over the last five years compared to an 18% increase in house prices in predominately urban areas. Furthermore, 13 of the top 20 local authorities for house price growth in 2021 are classed as rural.

But owning your own home in your rural communities isn’t the only answer. We need a mix of housing options so that there are affordable rental properties in our rural communities. Going back to the job market, wages earned in rural areas are lower than in urban areas, whilst the cost of living in rural areas is higher. Households living in rural areas have the highest fuel poverty rate of 15.9 per cent in 2022 and the largest fuel poverty gap at £956. Living in a rural area means you need a car to get around, as access to public transport is limited. Research in two English regions concluded that many small rural towns are at risk of becoming transport deserts, with 72 out of 110 small towns in the South West and 20 out of 50 in the North East already meeting this definition.

But there is a way out. Research commissioned by the RSN with CPRE shows that building ten new rural homes provides a £1.4m boost to disadvantaged local economies. I will let the maths do the talking:

- Ten new affordable rural homes cost just under £1.1m to build.

- This work directly supports the equivalent of around nine full time jobs in the construction sector.

This economic boost is multiplied along the supply chain so across the wider ecosystem:

- a total of 26 jobs are supported.

- £250,000 new tax receipted are generated.

- An overall £1.4m extra gross value added is created.

There are also savings to be had. Building new homes could bring workers into employment who would otherwise be unemployed and receiving benefits, saving the Government up to a further £12,000 per new home built.

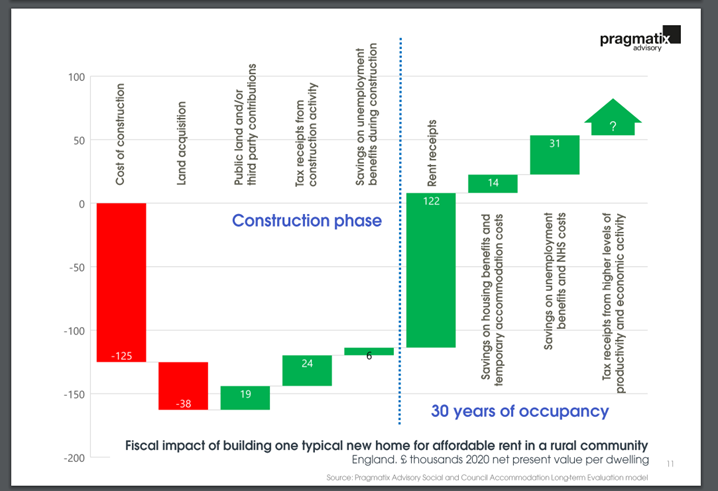

Central Government could also benefit. A programme of building affordable rural homes will improve public finances over 30 years by the equivalent of £54,000 per house in today’s money, even after taking account of the cost of construction and land acquisition.

|

So, the finances make sense, the benefits to local communities is clear, but crucially it is about the individuals. I return to the real-life stories from the research published at the beginning of this week. Stories from people who sleep rough and have to dig trenches in the snow to sleep, who go several days without food, who are spat on and their tents set on fire, who are victims of muggings which are so severe they result in brain injuries and teeth being knocked out. We pride ourselves on being a progressive country and yet this is happening on our doorsteps. The positive point is that answer is within our grasp. Let’s be brave enough to action.